Once again, seeking respite from the oncoming cold, I sought a diverting, undemanding film and chose How to Train Your Dragon 2 (2014; dir. Dean DeBlois). Brisk, vivid animation and the swooping, soaring exploits of flying dragons make for a significant entertainment. The film avoids many of the pitfalls of sequels. Although not as fresh as the original, this second installment of what may be a series follows the exploits of characters some five years after the first film as they take on the menacing dragon king Drogo. At the center of this film is the return of a parent who has been missing and presumed dead for twenty years. She reunites happily with her son and husband but then as you should always expect there are complications with consequences. In addition there is the discovery of a forgotten menace who reemerges to threaten the kingdom. (The success of this sequel may come from the series of books on which the two films are based). The characters in this film seem to be Vikings. They refer to themselves as Vikings, but there is a good bit of bagpipe music, and the chief’s sidekick Gobbo is voiced by Craig Ferguson, so perhaps these Vikings live in or near Scotland. The flying sequences are exciting, the battles loud and explosive, the comedy is about what you would expect—the film offers the usual array of comic secondary characters that seem almost de rigeur in films like this one. (What would Despicable Me be without those strange little eraser-like yellow sidekicks who follow Gru around?). Does the use of the Arabic numeral 2 instead of the Roman numeral II in this film’s title indicate some assumption about the film’s intended audience?

Once again, seeking respite from the oncoming cold, I sought a diverting, undemanding film and chose How to Train Your Dragon 2 (2014; dir. Dean DeBlois). Brisk, vivid animation and the swooping, soaring exploits of flying dragons make for a significant entertainment. The film avoids many of the pitfalls of sequels. Although not as fresh as the original, this second installment of what may be a series follows the exploits of characters some five years after the first film as they take on the menacing dragon king Drogo. At the center of this film is the return of a parent who has been missing and presumed dead for twenty years. She reunites happily with her son and husband but then as you should always expect there are complications with consequences. In addition there is the discovery of a forgotten menace who reemerges to threaten the kingdom. (The success of this sequel may come from the series of books on which the two films are based). The characters in this film seem to be Vikings. They refer to themselves as Vikings, but there is a good bit of bagpipe music, and the chief’s sidekick Gobbo is voiced by Craig Ferguson, so perhaps these Vikings live in or near Scotland. The flying sequences are exciting, the battles loud and explosive, the comedy is about what you would expect—the film offers the usual array of comic secondary characters that seem almost de rigeur in films like this one. (What would Despicable Me be without those strange little eraser-like yellow sidekicks who follow Gru around?). Does the use of the Arabic numeral 2 instead of the Roman numeral II in this film’s title indicate some assumption about the film’s intended audience?Sunday, November 16, 2014

How to Train Your Dragon 2

Once again, seeking respite from the oncoming cold, I sought a diverting, undemanding film and chose How to Train Your Dragon 2 (2014; dir. Dean DeBlois). Brisk, vivid animation and the swooping, soaring exploits of flying dragons make for a significant entertainment. The film avoids many of the pitfalls of sequels. Although not as fresh as the original, this second installment of what may be a series follows the exploits of characters some five years after the first film as they take on the menacing dragon king Drogo. At the center of this film is the return of a parent who has been missing and presumed dead for twenty years. She reunites happily with her son and husband but then as you should always expect there are complications with consequences. In addition there is the discovery of a forgotten menace who reemerges to threaten the kingdom. (The success of this sequel may come from the series of books on which the two films are based). The characters in this film seem to be Vikings. They refer to themselves as Vikings, but there is a good bit of bagpipe music, and the chief’s sidekick Gobbo is voiced by Craig Ferguson, so perhaps these Vikings live in or near Scotland. The flying sequences are exciting, the battles loud and explosive, the comedy is about what you would expect—the film offers the usual array of comic secondary characters that seem almost de rigeur in films like this one. (What would Despicable Me be without those strange little eraser-like yellow sidekicks who follow Gru around?). Does the use of the Arabic numeral 2 instead of the Roman numeral II in this film’s title indicate some assumption about the film’s intended audience?

Once again, seeking respite from the oncoming cold, I sought a diverting, undemanding film and chose How to Train Your Dragon 2 (2014; dir. Dean DeBlois). Brisk, vivid animation and the swooping, soaring exploits of flying dragons make for a significant entertainment. The film avoids many of the pitfalls of sequels. Although not as fresh as the original, this second installment of what may be a series follows the exploits of characters some five years after the first film as they take on the menacing dragon king Drogo. At the center of this film is the return of a parent who has been missing and presumed dead for twenty years. She reunites happily with her son and husband but then as you should always expect there are complications with consequences. In addition there is the discovery of a forgotten menace who reemerges to threaten the kingdom. (The success of this sequel may come from the series of books on which the two films are based). The characters in this film seem to be Vikings. They refer to themselves as Vikings, but there is a good bit of bagpipe music, and the chief’s sidekick Gobbo is voiced by Craig Ferguson, so perhaps these Vikings live in or near Scotland. The flying sequences are exciting, the battles loud and explosive, the comedy is about what you would expect—the film offers the usual array of comic secondary characters that seem almost de rigeur in films like this one. (What would Despicable Me be without those strange little eraser-like yellow sidekicks who follow Gru around?). Does the use of the Arabic numeral 2 instead of the Roman numeral II in this film’s title indicate some assumption about the film’s intended audience?Saturday, November 15, 2014

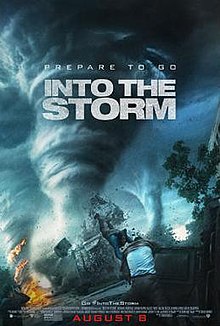

Into the Storm

Coming down with a cold, I wanted to sink down in my recliner and watch something that would require no real effort. That is, I wanted something brainless. My choice was Into the Storm (2013; dir. Steve Quayle), about a cluster of tornadoes that besiege the small town of Silverton, Oklahoma, one spring afternoon. I’d read the reviews that excoriate the film for its plotless implausibility. No doubt, the way the tornadoes behave in this film is probably not very consistent with observed meteorological realities, though the film evades the need for reality by having characters point out on various ways how “nothing like this has happened before.” Reed Timmer, the loud and in my opinion somewhat demented tornado chaser we’ve seen on Storm Chasers and other shows, insisted in an online essay that the film’s storms are realistic, if slightly exaggerated.[1] He also wrote a book about his storm-chasing experiences from which the film took its title. The loud and somewhat demented storm chaser whose crew are among the main characters in this film seems vaguely similar to Timmer and his storm chasing companions. So here we have monster tornadoes devastating a town, and what is the film’s focus? A young man estranged from his father; teenage romance; a storm-chasing meteorologist longing to be with her child. Father and son reconcile. Teenage romance blossoms. Mother and daughter reunite. Oddly, despite the movie’s insistence on the historical proportions of the tornadoes besieging Silverton, only a few people are actually blown to their deaths. There’s not much focus on the survivors either. There’s more concern with the aforementioned teenagers, the tornadoes, and their special propensity to wreak havoc. I have to admit that I was curious as to when certain characters would die. For the most part, I was disappointed. Of the main characters, only the loud and somewhat demented head storm chaser meets his fate in the monster tornado that blows him and his storm-chasing vehicle up into the heavens.

Coming down with a cold, I wanted to sink down in my recliner and watch something that would require no real effort. That is, I wanted something brainless. My choice was Into the Storm (2013; dir. Steve Quayle), about a cluster of tornadoes that besiege the small town of Silverton, Oklahoma, one spring afternoon. I’d read the reviews that excoriate the film for its plotless implausibility. No doubt, the way the tornadoes behave in this film is probably not very consistent with observed meteorological realities, though the film evades the need for reality by having characters point out on various ways how “nothing like this has happened before.” Reed Timmer, the loud and in my opinion somewhat demented tornado chaser we’ve seen on Storm Chasers and other shows, insisted in an online essay that the film’s storms are realistic, if slightly exaggerated.[1] He also wrote a book about his storm-chasing experiences from which the film took its title. The loud and somewhat demented storm chaser whose crew are among the main characters in this film seems vaguely similar to Timmer and his storm chasing companions. So here we have monster tornadoes devastating a town, and what is the film’s focus? A young man estranged from his father; teenage romance; a storm-chasing meteorologist longing to be with her child. Father and son reconcile. Teenage romance blossoms. Mother and daughter reunite. Oddly, despite the movie’s insistence on the historical proportions of the tornadoes besieging Silverton, only a few people are actually blown to their deaths. There’s not much focus on the survivors either. There’s more concern with the aforementioned teenagers, the tornadoes, and their special propensity to wreak havoc. I have to admit that I was curious as to when certain characters would die. For the most part, I was disappointed. Of the main characters, only the loud and somewhat demented head storm chaser meets his fate in the monster tornado that blows him and his storm-chasing vehicle up into the heavens.Monday, November 10, 2014

Star of the Sea, by Joseph O'Connor

A clear purpose of Joseph O’Connor’s novel Star of the Sea (Random House, 2004) is to present the suffering, prejudice, and mistreatment suffered by people of Ireland during the potato famine of the mid-19th century and more generally suffered at the hands of the English. The point of view shifts among an Irish maidservant, an Irish composer of folk ballads and also murderer, Pius Mulvey, an American journalist Grantley Dixon, and an English aristocrat David Merridith Lord who owns land on which he lives in Ireland. Others figure in as well, including Merridith’s father. The maidservant Mary Duane is at the center of the novel, but Merridith and Dixon are almost as important. Both have had affairs with her. All of these characters live entangled lives. This is an Irish novel, and although O’Connor gives us a range of English characters, some of whom he portrays with sympathy, his allegiances lie with the Irish.

This novel has many virtues and strengths. It is invariably interesting and engaging. It’s beautifully composed and structured. The characters are fully drawn in Dickensian fashion (Dickens himself makes a couple of appearances). But it gives as dark a story as one might imagine. Suffering and depravity are everywhere—in the streets of London, on the estates where Irish servants labor for British landowners, in the fields and ditches where Irish people die from famine and disease, in the hold of the ship, Star of the Sea, where Irish refugees are transported to America in hopes of an improved life, and in the American harbor where the ship, along with many others carrying Irish refugees, lingers for days waiting to be allowed to unload their passengers, who perish in growing numbers with the passage of each day.

O’Connor wants his reader to appreciate the enormity of the largely overlooked potato famine, which caused the deaths of as many as a million people, and from which as many as two million Irish citizens fled to the United States and other parts of the world. The consequence for Ireland and those who remained behind was devastating.

The message overwhelms the artistry of the book at times, if it is possible to extricate one from the other, and the book reads occasionally like a political tract, a work of historical documentation. This is understandable. The horrors O’Connor recounts, the suffering and racism, may be too fraught for fiction to bear. The historical events at the core of this novel are so appalling that fictionalizing them seems to trivialize them.

Tuesday, November 04, 2014

Gabrielle

Two questions concerning Gabrielle (2013; dir. Louise Archambault): Does the film succeed, as I think it means to, in conveying the inner life of a young women with Williams syndrome, a genetic disorder that leaves one partially incapacitated in certain cognitive and physiological ways. Does the film unethically lead its main actor, a woman afflicted with Williams syndrome, to engage before the camera in the representation of activities that she does not fully understand? The main character, played by Gabrielle Marion-Rivard, is a highly functional victim of the syndrome. She communicates well, is full of enthusiasm and affability (as are many Williams syndrome patients), but also cannot handle certain tasks—such as testing her blood sugar each day, or navigating her way through Montreal by bus. Although she wants to live on her own, she needs assistance. She receives help from her sister Sophie, and the caregivers at the center where she lives. Her parents are alive, but we never see her father, and her mother is strangely distant and unengaged. Gabrielle is a lovely young woman. The film helps us appreciate her many qualities along with the difficulties she would face in leading a normal life.

Gabrielle’s desire to live her own life becomes a significant issue for her when she falls in love with Martin, a young man who takes classes at the same center as she does. Martin is also intellectually challenged, but he seems somewhat better adjusted that Gabrielle. As the film progresses, the two of them move towards a physical relationship. Martin’s mother does not believe her 24-year-old son is ready for sex, and when she discovers Gabrielle and Martin partially unclothed together; she removes him from the school. Later the two reunite at a performance of the chorus they belong to, and they consummate their love beneath the grandstands of the concert arena. Gabrielle portrays this moment in a relatively tasteful and discreet way.

How much did Gabrielle Marion-Ricard the actor fully understand what she was doing? Could she make an informed decision about participating in the scene. Do not misunderstand: people like Gabrielle and Martin are entitled to love one another, to have sex—in real life and on film. But did the actress fully understood the role she was portraying, the scene in which she had sex with Martin?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)