Every now and then I encounter a book or film or painting that lacks a point of reference, an identifying marker or set of markers within the literary or cinematic or art worlds that allows me to place and understand it in comparison to other books or films or paintings. Sometimes—perhaps most of the time—this is the fault of my own ignorance. Perhaps other times the fault belongs to the work itself—to shoddy form or unfocused vision or downright ineptitude. Occasionally it is the result of a distinctive and original artistic vision. Sometimes the reason is just not clear.

For much of Sherman's March: A Meditation on the Possibility of Romantic Love in the South During an Era of Nuclear Weapons Proliferation (1986, dir. Ross McElwee) I thought I was watching a self-indulgent and long-winded home movie. This film is really about another film. The director Ross McElwee begins by announcing that he wanted to make a film about the impact of Sherman’s campaign on the Southeast, especially Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina. But just as he was about to begin, he tells us, his girl friend broke up with him, leaving him hurt and traumatized. So instead he makes a film about a quixotic odyssey in search of a romantic partner that takes him through the states through which Sherman marched. Occasionally, he actually talks about Sherman, a man with whom he finds much in common. Sherman for much of his life regarded himself as a failure, a judgment the director levies on himself as well. Following the end of the war, Sherman was criticized for negotiating a surrender with the South in his campaign that was too lenient, and he was treated unfairly. Sherman loved the South, lived there much of his life, and so when he was ordered to wage his campaign of destruction, McElwee finds that fact highly ironic. McElwee believes Sherman was a brilliant writer. By overt connection and implication, he finds much in common with the Civil War general.

But Sherman occupies only a relatively short portion of this two-hour and thirty-seven minute film. Most of it is taken up with what at first appears to be casual and amateurish footage of the director’s visit with his parents and with various women whom he has been involved with in the past, or whom his parents or friends try to fix him up with, or whom he just happens across. Mostly they are in their late twenties or thirties, like him, and like him they are trying to find their place in life. Several aspire to be actresses, one wants to be a singer, another is a Mormon who wants to bring God into her house through marriage, another is a linguist living on Ossabaw Island working on her dissertation, another is an anti-nuclear power activist and teacher, and another is a lawyer in an off-again, on-again relationship with a man.

McElwee easily becomes infatuated with these women, but he seems fairly inept at relationships. This is one of the points of the film, which features McElwee’s attempts to discuss with the various women their reasons for lack of interest in him. In part he blames his own mistakes and weak character. Several women are more interested in their careers than in him. He and the linguist become involved in their idyllic Ossabaw Island setting, for a time, but then he leaves for a part-time job in Boston and she finds someone else. The women with whom he was involved in the past aren’t really interested in rekindling the former connection—they’ve moved on. In part, he blames the nuclear age. How can he sustain a relationship at a time when the threat of nuclear destruction looms constantly in mind?

McElwee portrays himself as a kind of Southern Protestant nebbish. He’s romantically inept and miserable as a result. He’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. At the end of the film, having failed at romance, he announces that he doesn’t really like the South and travels north to make films and teach filmmaking at Brown University, where he teaches today. With this pronouncement, the end of the film has the effect of subverting in an amusing and ironic way McElwee’s sense of failure and incompetence. He’s clearly good at something.

McElwee defines his own documentary style in Sherman’s March. It’s not a style that could easily be imitated, and indeed, given the length of this film, not one with much commercial potential. It’s a style that is obviously a projection of McElwee’s personality. Despite the casual, deliberate sloppiness to the film, there is a clear method at work, one that parallels the route of Sherman’s march with McElwee’s own romantic odyssey, and that portrays an interesting series of Southern characters—mostly white and female, affluent to varying degrees (with one exception)—at a time when the South was becoming increasingly urban and suburban, deracinated, deregionalized.

A minor sort of theme in the film involves Burt Reynolds. The first woman whom McElwee encounters in the film (in a meeting arranged by his father and step-mother) is an aspiring actress who has a connection with a friend who works for Burt Reynolds. She hopes to wrangle a part in a Reynolds film. Later in the film, McElwee actually runs across the set of a Reynolds film (Stroker Ace? Cannonball Run II?) and tries to film Reynolds but is thrown off the set and threatened with arrest. Does Reynolds represent the authentic South?

In a sense, as a filmmaker from Boston who comes down South to make a film about a man known for his destructive campaign in the South, McElwee joins with those forces that are changing the South in as drastic and fundamental a way as Sherman ever managed to do. The film shows several vistas of the skyline of Atlanta, Columbia, SC, Savannah, and Charlotte during the mid-1980s. These cities represent the South’s recovery from Sherman’s March, and at the same time the long-term and undeniable impact of the victories he achieved.

(In my favorite scene, McElwee walks towards the banks of the Congaree River, in Columbia, SC, gazing at the city skyline. He tries to clamber down the banks towards the river but falls, disappearing from view. The image of this awkward, bumbling figure trying to negotiate the Southern landscape is representative of his demeanor in the film as a whole).

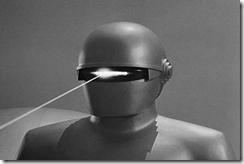

is clear. (The idea of subtlety in the 2008 film is a truly alien concept). In the older film we are told that the robot Gort can destroy the world, if called on to do so. We are shown only a few minor examples of his power. He is a frightening and imposing figure, and there is no doubt that he is formidable. But this is clear only because of implication. In the later film we are also told that Gort can destroy the world, and then in graphic and considerable detail for the last twenty or so minutes of the film we are shown how he can do so. The trouble is that I never believed in the robot of the newer film—he looked like a special effect from the beginning, and when he starts in on his destroy-the-world shtick, all I could think to myself was, "these are special effects." Gort in the newer movie lacks the mystique and reality of Gort in the older film. He is an abysmal failure.

is clear. (The idea of subtlety in the 2008 film is a truly alien concept). In the older film we are told that the robot Gort can destroy the world, if called on to do so. We are shown only a few minor examples of his power. He is a frightening and imposing figure, and there is no doubt that he is formidable. But this is clear only because of implication. In the later film we are also told that Gort can destroy the world, and then in graphic and considerable detail for the last twenty or so minutes of the film we are shown how he can do so. The trouble is that I never believed in the robot of the newer film—he looked like a special effect from the beginning, and when he starts in on his destroy-the-world shtick, all I could think to myself was, "these are special effects." Gort in the newer movie lacks the mystique and reality of Gort in the older film. He is an abysmal failure.